My desire is to build great guitars for great players.

When we talk about your next guitar, the discussion is about your music, your playing, and your requirements.

I start by completely understanding your demands on a guitar; your style and repertoire, your strengths and limitations, the sounds that you desire.

Together, we’ll discuss the options available in order to build an instrument that poses the minimum impediment between you and your repertoire.

I advise on instrument type and wood selection and we agree on what the instrument will look and sound like.

I select specific pieces of your chosen timbers based on their measured acoustical properties.

Then, using the design techniques that I have developed, I determine the thickness of the top and back, and the sizes and distribution of the braces that will deliver the sound that you seek.

We select the finish that will best suit the environment in which the instrument will spend its working life.

Within a few short months from the commencement of build, you will take delivery of the new guitar and delight in its performance.

Welcome, and please take a leisurely look around my website. Check out some of the guitars that I’ve built and how I go about it. You’ll see that I do things a bit differently.

Playability

Playability covers the range of physical attributes of a guitar and how those attributes impinge on the player.

A guitar with poor playability will never bring out the best in a guitarist.

Factors affecting Playability

The factors that affect playability include:

- The body size and shape

- The spacing of the strings at the nut and saddle

- The neck’s profile

- The scale length

- The guitar’s tuneability

- The string height at the nut and the twelfth fret

- The fretboard’s radius of curvature

- The neck’s relief

- The finish on the back of the neck

- How the neck blends into the fretboard

- The spacing of the strings from the fretboard edge

- The number of frets and their size

- The number of frets to the body joint

- Whether or not the cutaway is incorporated

- and so on…

It’s definitely not “one size fits all”. Of necessity, the factory builders have adopted a set of playability factors which many players find adequate, but are hardly optimal for specific individuals.

Your guitar and Playability

I am a custom builder, so you get to choose what I build for you, rather than you choosing from a narrow range of offerings. The range of playability factors and their permutations may seem mind boggling; however, I see it as part of my job to help you through that, so you make the best choices for how and what you play; to make playing your repertoire as easy as possible.

That, really, is what playability is all about. Being able to nail your chops every time, without “killing” yourself.

Musicality

Musicality is everything about how a guitar sounds.

The picture above shows one of my compensated nuts on a classical guitar.

Compensating the nut as well as the saddle is another significant contributor to the musicality of a guitar.

Until I figured out the physics and engineering of this, I hadn’t realised how much better a guitar could sound.

The challenge is to articulate what that means in terms of the acoustical properties of the guitar and how these properties relate to the woodwork.

It begins with an understanding of consonance and dissonance; what harmonic content of a string sounds good to you and which harmonics you can best do without, and then making sure they don’t get in the way of the “good” harmonics.

It’s about understanding how to get the string’s harmonics not only to play in-tune in and of themselves, but to play in-tune with other strings. That’s in-tune to the equally tempered scale.

Why is this important?

Because the more of the right harmonics you have playing in tune across all the strings, the clearer the tone, the better the note separation and the better the pitch accuracy you perceive.

This adds up to a guitar that sounds a whole lot better than most others, because precious few guitars play anything like in-tune.

Single notes are clear and translucent, chords are sweet and articulate.

So what’s different about Trevor Gore guitars?

My guitars are built with a very clear understanding of the interaction between the string resonances and the guitar’s body resonances; its air resonances and its wood resonances.

If you shift the pitch of a body resonance, it will react differently than before with the resonating string, shifting the pitch of the string’s fundamental frequency and its harmonics.

So if you don’t pitch the body resonances in the right place as part of the design and build process, you have a guitar that never plays properly in-tune, which is pretty much where most guitars sit and why mine are different.

But there’s more to it than keeping things consonant. Where it gets really hard is achieving consonance (“in-tuneness” across all the strings) with responsiveness, evenness and volume, all at the same time. That, in a nutshell, is what the book is all about.

Technical

I’m hoping I haven’t used too much technical jargon in describing my design techniques! However, I do get enquiries about technical matters from readers who are interested in these things and can’t wait for the book to land on their doorsteps!

There follows various downloadable papers, articles and technical descriptions/definitions.

Acoustical Society of America – Wood for Guitars

Due to my scientific approach to guitar design, I was invited to submit a paper to the Acoustical Society of America conference in Seattle, held in May 2011. Titled “Wood for Guitars”, the paper discusses the use of a wide variety of woods used in guitar building and the influence they exert on the guitar’s structural and acoustical performance. The paper was very well received. Here’s the abstract:

Wood for guitars

“Numerous famous luthiers have used low grade salvaged timber and non-wood products to demonstrate that how a guitar is designed to exploit available materials is more important than using prime tonewoods. The material properties of timber are highly variable and are not the single figures frequently quoted in reference books. Within-species material properties can vary by a factor of two.

Consequently, there is significant overlap of the material properties of one species with others, implying that wood species substitution is possible with little acoustical impact if the component is designed and built to acoustical tolerances rather than dimensional tolerances.

However, species selection remains a significant factor in designing guitar components, primarily for structural rather than acoustical reasons. The woods chosen have to survive long-term loading without excessive distortion over time whilst still allowing the radiating surfaces to vibrate freely. Important parameters include Young’s modulus, density, stability with humidity variation, heat bendability, and hardness.

The author considers wood for soundboards, braces, backs, sides, necks, fretboards, and bridges. Guitars designed to acoustical criteria (rather than dimensional criteria) where the effects of different stiffnesses and densities of species are minimised, sound very similar.”

The full text of the 20 page paper can be downloaded from “Wood for Guitars”, or from the ASA Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics website, via this link.

Definition – Monopole mobility

Monopole mobility is a measure of the responsiveness of a guitar and is (broadly speaking) a measure of the admittance of the main monopole mode of vibration.

This vibrational mode is generally the most active and is the mode that is responsible for radiating most sound. The measure is a combination of the effective stiffness K of the mode and its effective mass m.

A good guitar (to my way of thinking) has its mode frequencies in the right place and has high monopole mobility, where monopole mobility is proportional to 1/sqrt(Km).

Sound Spectrum Analysis

There is a wide variety of software spectrum analysers available. One that I use frequently is called Visual Analyser and the directions regarding how I set it up can be downloaded by clicking Setting up Visual Analyser.

Additionally, in conjunction with Robbie O’Brien, I produced a video series explaining in more detail how to set up Visual Analyser and how to conduct the testing I routinely do.

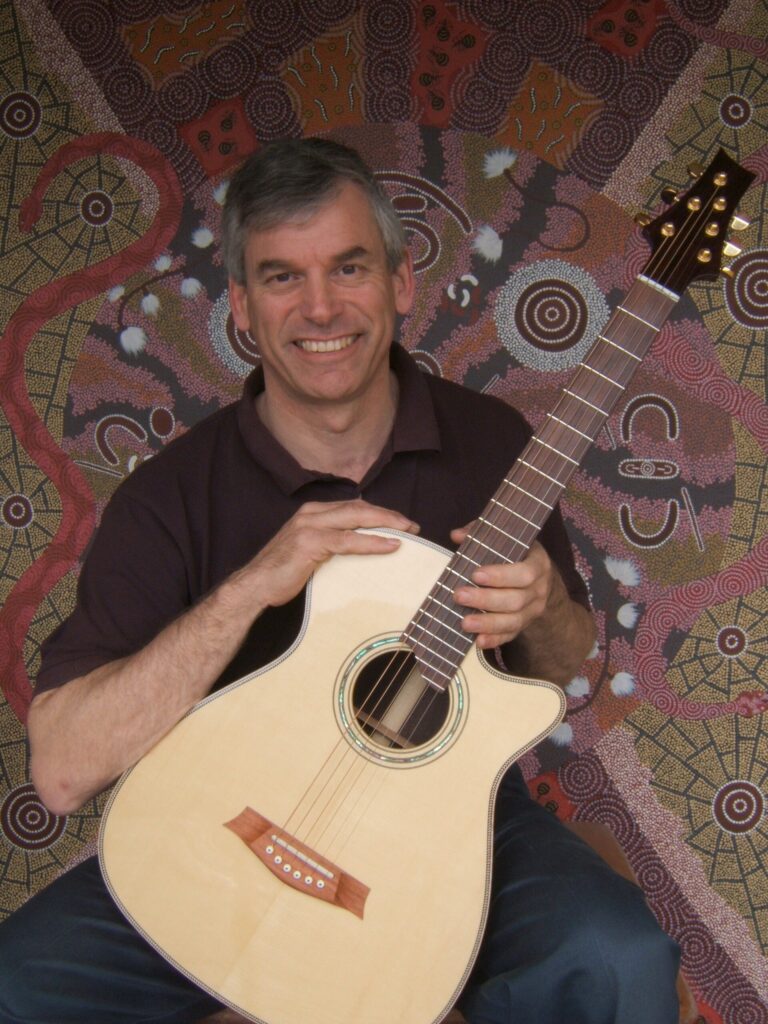

Biography

The early days

My interest in guitars started around age seven, when, exploring in the attic as small boys do, I came across my father’s arch-top guitar, a 1929 copy of a Gibson L5.

Shame it wasn’t a real one! It had a beautiful sunburst finish which positively glowed and even though there was no way I could extract anything musical from it then, the addiction was immediate.

I learned to play using that guitar, and in my hands it suffered many ignominies, including nylon strings, and homemade pick-ups (made from a set of WWII ex-army headphones).

It was many years later that I rebuilt it and reset its sagging neck, and passed it on in near perfect condition (despite all my efforts as a teenager) to one of my nephews who had inherited the musical gene.

My interest in guitars was interleaved with interests in sports (particularly sailing) and woodwork, with educational and professional commitments mainly in engineering fields distracting me occasionally.

I graduated from Durham University in the UK with a Bachelor’s degree in engineering followed by a PhD.

I worked post-doc for a while at Cambridge University Engineering Department teaching students the complexities of applied mathematics and electromagnetism (or were they teaching me?).

Over that period I built numerous wooden boats and raced them with considerable success. The boat building certainly honed my woodworking skills and the engineering disciplines were ever useful.

Experimenting with acoustics and guitar building

Fast forward a few years, with an MBA behind me and a good many years of consulting engineering, I was still playing guitars and sailing boats. But now I was living in Australia – the result of too many consulting assignments to this part of the world.

So I bought a cheap second hand guitar to play on my cheap second hand boat and found it somewhat lacking. The saddle was in the wrong place.

Not being sure that there would be enough room in the bridge to reposition the saddle, I wrote a small computer program to figure out where the saddle had to go so that the guitar would play in tune (spot the engineer).

Having found the saddle position that allowed the guitar to play in-tune on the open strings and the 12th fret, I wondered how in-tune it played on all the other frets.

So I modified the program and discovered essentially what I already knew: most guitars play out of tune on most frets most of the time. I modified the program again to figure out how to correct that and discovered the concept of compensating both the nut and the saddle.

Probably not a new idea, but I hadn’t come across it before. How to find out if this would work? Some significant carpentry was required on the nut end of the fretboard as well as the bridge.

Easier to build a new guitar. So I did, and the rest, as they say, is history.

How Gore Guitars was formed

My dissatisfaction with store bought guitars (even “good” ones) made me think that there had to be a better way of designing and building them.

The popular literature on guitar acoustics (read: guitar company marketing propaganda) was pure voodoo physics, so a good deal of digging about in research papers was required as well as conducting my own research and development program.

The copious notes I made turned into a book, which was first published in 2011. I hope the brief explanations on this website of how I work will excite your interest in seeking a better guitar and hopefully lead you to trying one of mine.

After all is said and done, it’s what they play like and what they sound like that really matters.

(Oh, and all my guitars, both classical and steel string, have compensated nuts and saddles.)

Thanks for your interest,

Trevor Gore

Member: Acoustical Society of America

Member: Guild of American Luthiers